Signals Not Scandals

- awalker187

- Dec 2

- 4 min read

The B-17 Flying Fortress was the main US heavy bomber of WW2.

It was an incredibly successful design.

12,731 were built and they dropped more bombs than any other aircraft in the war.

They were rugged, stable, and capable of sustaining incredibly heavy damage and still return home.

But they had a major issue.

The pilots kept breaking them.

Throughout the war stressed, tired and confused pilots would land their planes and then suddenly retract the wheels.

The planes would crash to the ground, destroying engines, wings and propellers, destroying the plane.

And almost every time the reports would show that it was caused by “pilot-error”.

To err is human

Two years after the war, the psychologists, Paul Fitts and Richard Jones, were asked to take a look at this strange behaviour.

They analysed over 460 cases of “pilot-error”.

They expected to find a certain type of pilot who was more accident prone.

They’d be the sort of people that would make a number of random mistakes when flying or landing.

What they actually found was that every type of pilot were making exactly the same mistakes.

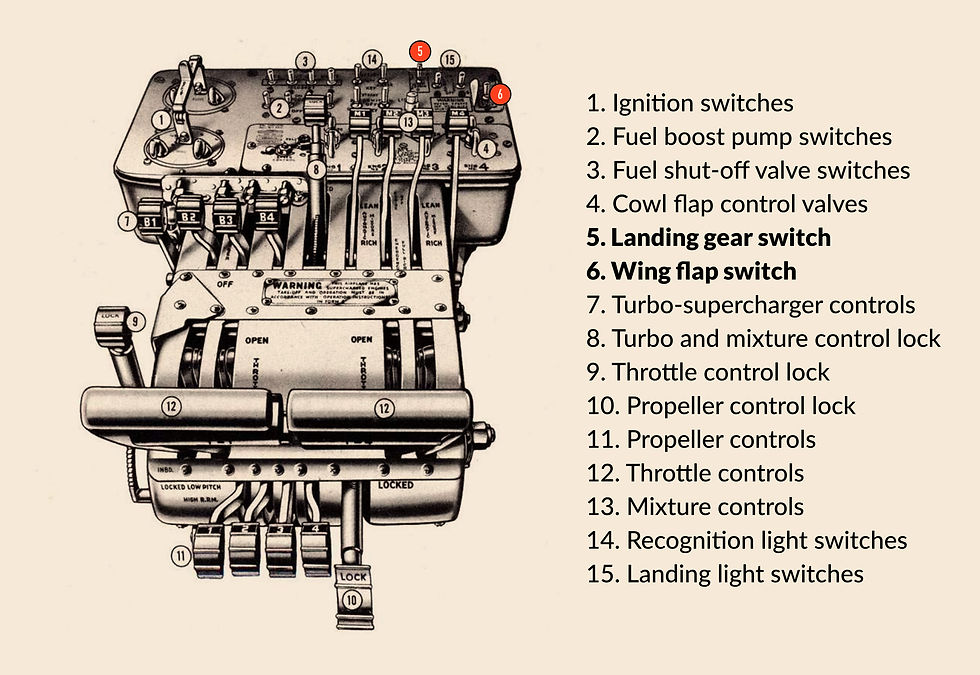

As the exhausted pilots approached the runway, they would flip a switch to drop the wheels down and a switch to lower the wing flaps to slow the plane.

Then when they had landed they’d reach out for the switch to raise the wing flaps again.

But they’d accidentally toggle the switch for the landing gear instead.

And the plane would pancake to the ground.

The psychologist and industrial designer, Alphonse Chapanis (who later designed the keypad for push button phones) was the man asked to investigate why and find a solution.

Instead of “pilot error,” he soon realised that the problem was, “designer error.”

“A great many accidents result directly from the manner in which equipment is designed and where it is placed in the cockpit,” he wrote.

The two different toggle switches were identical and positioned almost next to each other.

For exhausted pilots that mistake was just too easy to make.

A bad system will beat a good person every time.” - W. Edward Deming

Chapanis recognised that the problem could be prevented entirely with better control designs.

And his “ad hoc remedies” introduced the world to the idea of ‘shape coding’.

He replaced the use of identical controls with knobs and levers that mimics the form of the things they controlled.

Now the wing flaps lever would be shaped like a wing, and the undercarriage lever would shaped like a wheel.

He also made sure that the different controls were now placed further apart.

So now when a pilot is landing the plane there's no chance of confusion, even when they’re tired, stressed or even if they're operating in pitch black.

The designs worked so well that they’ve become coded laws and you’ll see them in the cockpits of all modern planes.

“You have a problem, you are not the problem.” - Alan Mulally, former Ford CEO

Check this

The B-17 also had another impact on how how systems are designed today as the result of another crash.

In 1935 one of the very first prototypes crashed in a test flight killing both of the pilots.

The investigation found that the pilots had forgotten to turn off the gust locks before the flight.

Gust locks are devices that stop the control flaps from moving in the wind when parked.

And with the flaps locked in place, the pilots had no control and the plane crashed directly after take off.

Again the could have been chalked down to a simple pilot-error, but the team at Boeing realised that it could be prevented.

They designed a checklist for all pilots to use before takeoff to avoid potential errors like this.

It was the first preflight checklist.

Another simple, but brilliant idea that helped make flying significantly safer for everyone.

Checklists are now used everywhere from medicine to manufacturing, from construction to customer service, to reduce errors, ensure consistency, and improve efficiency.

To err is systemic

“Guns don't kill people, rappers do, Ask any politician and they'll tell you it's true,” - Goldie Lookin Chain

We’re conditioned to seek “pilot error”, or for most of us “human error”, and stop there.

It feels like an answer, but it’s a dead end that leads to repeated failure.

We have to challenge ourselves to go deeper and ask, “What allowed this to happen in the system?”

Problems should be signals, not scandals.

And when you identify the problem, or even better anticipate it, you have to design for imperfection.

Or as the man who they named ‘Norman doors’ after says:

“The idea that a person is at fault when something goes wrong is deeply entrenched in society. That’s why we blame others and even ourselves. Unfortunately, the idea that a person is at fault is imbedded in the legal system. When major accidents occur, official courts of inquiry are set up to assess the blame. More and more often the blame is attributed to “human error.” The person involved can be fined, punished, or fired. Maybe training procedures are revised. The law rests comfortably. But in my experience, human error usually is a result of poor design: it should be called system error. Humans err continually; it is an intrinsic part of our nature. System design should take this into account. Pinning the blame on the person may be a comfortable way to proceed, but why was the system ever designed so that a single act by a single person could cause calamity? Worse, blaming the person without fixing the root, underlying cause does not fix the problem: the same error is likely to be repeated by someone else.” - Donald A. Norman, The Design of Everyday Things

Fitts, P. M., Jones R. E., “Analysis of Factors Contributing to 460 “Pilot-Error” Experiences in Operating Aircraft Controls”, Army Air Forces Headquarters, Air Material Command, Engineering Division (1947)

Chapanis, A., “The Chapanis Chronicles: 50 Years of Human Factors Research, Education, and Design”, Aegean Pub Co (1999)

“Pilot Training Manual for the Flying Fortress B-17”, Headquarters, AFF, Office of Flying Safety (1944)